The Materials Race Behind Solid-State Batteries

Solid-state batteries are often described as the next major leap in energy storage¹. They promise faster charging, improved safety, and higher energy density compared to today’s lithium-ion systems¹. Yet the true challenge is not only the cell architecture. It is the materials ecosystem required to make these batteries scalable, stable, and commercially viable².

This post looks at the materials race behind solid-state batteries, why new chemistries demand new supply chains, and how specialty materials will shape the path from lab-scale cells to industrial production.

Why Solid-State Batteries Require a New Materials Landscape

Conventional lithium-ion batteries use a liquid electrolyte that moves ions between electrodes. Solid-state batteries replace this liquid with a solid electrolyte that must still conduct ions efficiently while remaining mechanically and chemically stable¹.

That change ripples across the entire bill of materials². Solid-state designs often require:

- solid electrolytes with high ionic conductivity²

- interface stabilizers between electrolyte and electrodes²

- lithium metal or other high-capacity anode materials¹ ²

- nickel-rich cathodes tuned for higher energy density¹ using nickel metal

- protective ceramic or oxide coatings³

- structural materials that can tolerate pressure and temperature swings⁵

Each of these materials comes with tighter purity requirements, different processing conditions, and new failure modes compared to liquid electrolyte systems². Lithium becomes especially important in many solid-state concepts because it enables much higher energy density than graphite-based anodes¹.

The Solid Electrolyte Challenge

Solid electrolytes sit at the center of solid-state battery performance. They must:

- conduct lithium ions rapidly¹

- remain stable across operating voltage and temperature²

- resist decomposition at interfaces²

- tolerate mechanical stress and cycling⁵

Most current research clusters around three main electrolyte families²:

Oxide Electrolytes

Oxide ceramics provide excellent thermal stability and relatively benign failure behavior². They can support high-voltage operation and are generally compatible with a wide range of cathode materials¹. The tradeoffs include:

- high-temperature sintering requirements³

- challenges producing dense, defect-free layers³

- brittleness that complicates assembly and cycling⁵

Sulfide Electrolytes

Sulfide materials offer very high ionic conductivity and can often be processed at lower temperatures². They can be cast, pressed, or co-sintered into relatively thin layers². Their main challenges include:

- sensitivity to air and moisture³

- gas generation and interface reactions if not properly protected³

- need for very clean, controlled precursor streams³

These include sulfide compounds such as cobalt(IV) sulfide (https://reade.com/product/cobaltiv-sulfide-cos2/).

Polymer and Hybrid Electrolytes

Polymer-based systems are attractive from a manufacturing standpoint². They can be processed with techniques close to existing battery production and can be combined with inorganic fillers or layered structures². Their limitations are:

- lower ionic conductivity at room temperature²

- more complex pathways to match ceramic electrolyte performance²

In practice, many emerging designs explore hybrids that blend the strengths of these categories².

The Interface Problem

Even when a solid electrolyte performs well on its own, the interfaces with the anode and cathode are often where real-world problems appear¹ ². These contact zones must maintain:

- good ionic and electronic pathways¹

- mechanical contact through thousands of cycles⁵

- resistance to unwanted side reactions¹ ²

Key failure mechanisms at interfaces include:

- formation of resistive layers that slow ion transport²

- microcracking or delamination as materials expand/contract⁵

- uneven lithium deposition causing localized damage¹

- changes in crystal structure at high voltage or temperature²

Engineering these interfaces can involve:

- thin protective coatings on cathode particles³

- tailored surface chemistries on solid electrolytes²

- compliant interlayers that accommodate movement¹

- careful control of stack pressure and assembly conditions³

Nickel-rich cathodes nickel and lithium metal both place additional stress on these interfaces due to their high reactivity and volume changes².

The Cathode Bottleneck

To reach the energy density targets that make solid-state batteries compelling, most designs rely on high-nickel cathodes². These materials deliver strong specific energy, but they are demanding from a materials and engineering perspective.

Solid-state implementations must address:

- surface reactivity between nickel-rich cathodes and solid electrolytes¹ ²

- structural changes in cathode particles at high voltage²

- gas generation and interface instability during cycling³

- the need for ceramic or oxide coatings that remain intact for the full life of the cell³

Coating chemistry, particle morphology, and microstructure all become critical levers³.

The cathode is no longer just a “drop in” material reused from liquid electrolyte systems; it has to be co-designed with the solid electrolyte and interface strategy².

Key cathode-related materials include cobalt metal (https://reade.com/product/cobalt-co-metal/) and nickel metal (https://reade.com/product/nickel-ni-metal/).

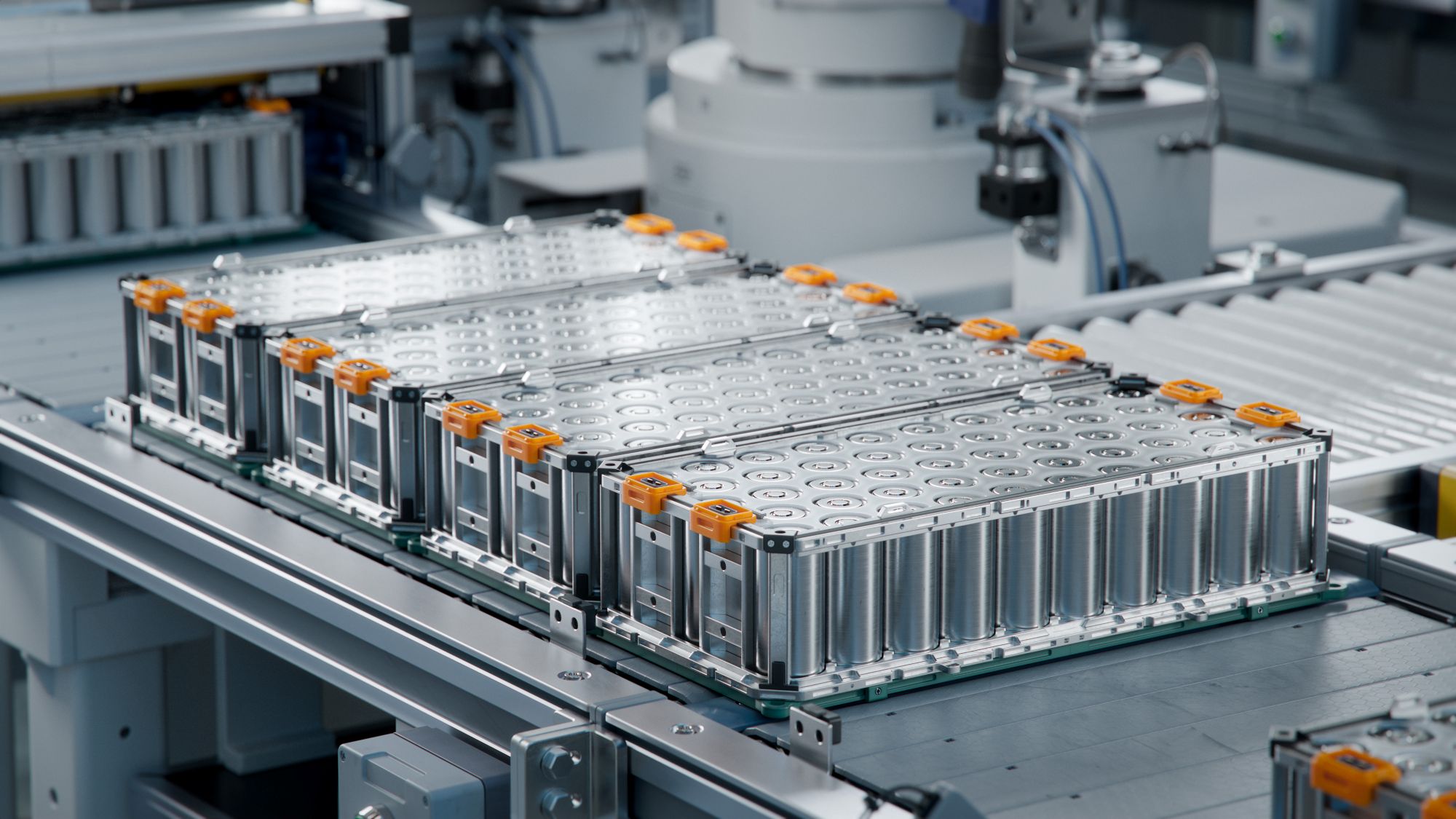

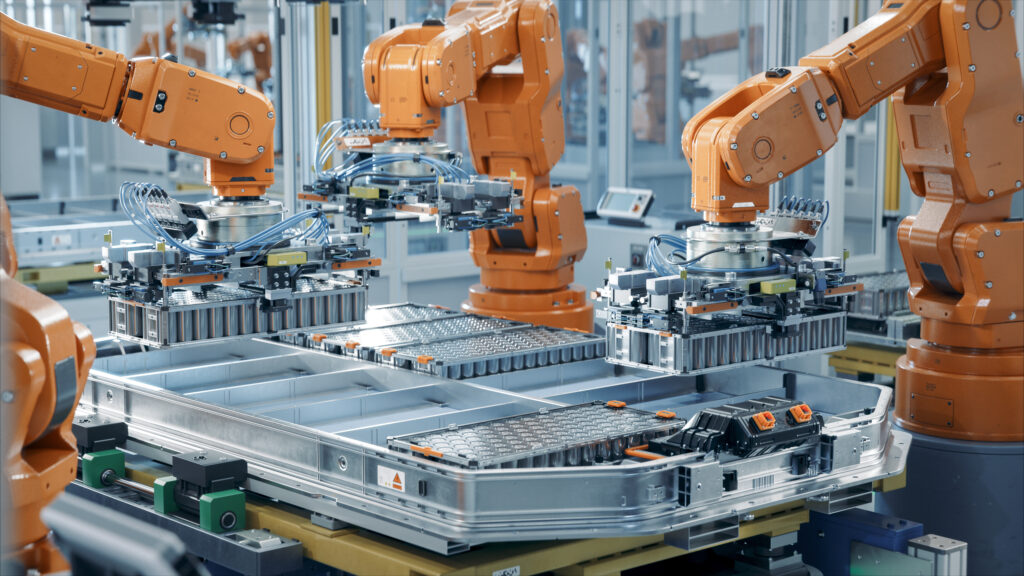

Scaling Manufacturing: The Hardest Part

Even when a solid-state chemistry looks promising in small test cells, scaling it into a repeatable manufacturing process remains one of the largest obstacles³.

Solid-state production typically involves:

- dry room or very low humidity environments³

- precise pressure control during stacking and lamination³

- sintering or densification steps for ceramic components³

- tight tolerances on thickness and surface quality³

- strict contamination control in powders and films³

Minor defects that a liquid electrolyte might “bridge” can be fatal in a solid-state stack³. Voids, cracks, and local thickness variation at interfaces can quickly lead to performance loss or early failure⁵.

On top of that, the upstream supply chain must be able to deliver:

- high purity lithium and other critical metals

- consistent sulfide and oxide precursors such as cobalt(IV) sulfide

- ceramic powders and additives with very controlled particle size distributions³

All of this must come together at a cost point that can compete with rapidly improving conventional lithium ion cells¹.

Why Materials Supply Will Decide the Winners

The race to commercialize solid-state batteries is not just a race of electrochemical concepts or clever architectures. It is a race to secure and integrate the right materials at scale² ³.

The companies and research programs that pull ahead will likely be those that:

- lock in stable sources of high purity lithiumand other critical materials

- build trusted relationships with suppliers of electrolyte and cathode precursors³

- collaborate closely with materials partners to refine microstructure and interfaces²

- design processes that tolerate real-world variation while still meeting performance targets³

In other words, progress will depend on the strength of the materials ecosystem as much as the cell design itself¹.

Advancing Materials Engineering for Solid-State Batteries

Solid-state batteries introduce engineering challenges that run through every layer of the cell¹,⁶. Interface stability, mechanical reliability, and feedstock consistency all matter as much as nominal ionic conductivity or theoretical energy density.

Progress will depend on materials suppliers and research teams working together to refine individual components and how they interact under real operating conditions¹ ².

Reade supports this evolution by supplying high specification lithium materials, cobalt and nickel metals, and sulfide compounds used in solid-state electrolyte and cathode research. These materials help researchers and manufacturers explore new electrolyte formulations, test interface strategies, and push the performance of next generation solid-state batteries closer to commercial reality.

References

¹ https://www.mdpi.com/2313-0105/11/3/90

² https://www.mdpi.com/2313-0105/10/1/29

³ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590116824000614

⁴ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666539523001694

⁵ https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.05294

⁶ https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.09434